By Benedetta Casagrande

Developed between 2010-2017, Peter Watkins’ project The Unforgetting looks at the photographer’s German family history and at the trauma of the loss of his mother as a child. ‘The Unforgetting’ could be understood either as a noun or as a verb. Whilst the former refers to ‘he/she who does not forget’, reflecting the storage of a passive, crystallized set of memories whose symbolic and affective meanings are predetermined (much like in Lois Lowry’s dystopian children novel The Giver), the latter points to an active process of reversal of forgetting; an undoing of a state of oblivion defined by fluidity, movement and the negotiation of meaning. Watkins’ project and recent photobook belongs to the second definition. But how does one reverse the process of forgetting? To distill memory in retrospective necessarily means to rely on partial narratives (provided by objects, family members and documents) which gaps and discontinuities allow a space for agency, whilst nonetheless pointing to the irretrievable nature of that which has been forgotten.

Developing around Watkins’ investigation of those memories which compose ‘the lining of forgetting’ [1], the photobook is largely comprised by still lifes of objects that belonged to his mother, Ute, as well as objects and photographs that belonged other family members. Looking at his monumental compositions I found myself reflecting on my relationship to the objects that belonged to those who I loved and lost. Whilst I am lucky enough to still have my mother, I lost my oldest brother when I was nine years old. The memories of him are scarce; the objects I possess of him are even less. The only objects I have access to are an oversized pullover, a faded bracelet made of wooden beads and a camera that my sister recently gave me and which I still did not find the courage to use. The bereavement of his loss was supplemented by the bereavement of his objects; throughout my growth I was accompanied by the feeling that I had been deprived of the instruments I needed to discover my brother and build a posterior intimacy with a man I used to love and who, today, I am unable to tell if I have known or not.

I share this not to relate my experience of loss to Watkins’ experience, but to take a closer look at objects as centrepieces of our emotional and intellectual life. In Watkins’ project objects are pivotal in the process of unforgetting. Yet, none of the totemic assemblages presented to us provide an access to memory; the social biographies of the photographed objects remain unknown to the viewers unless they decide to engage with the many texts written about the project, which shed light on some of their stories. Rather, Watkins’ assemblages recall Lévi-Strauss’ ideas of bricolage - a way of combining and recombining a closed set of materials to develop thought.

“The bricoleur [...] derives his poetry from the fact that he does not confine himself to accomplishment and execution: he ‘speaks’ not only with things [...] but also through things. The bricoleur may not ever complete his purpose, but he always puts something of himself into it.” [2]

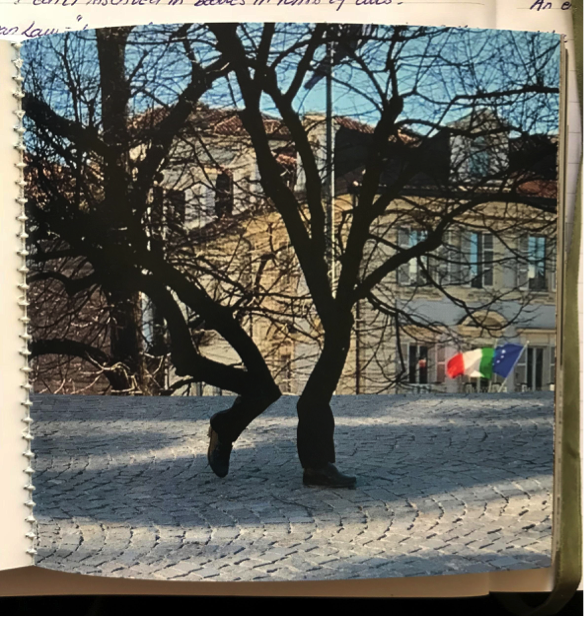

A spread from the book

In Genetic Epistemology, Jean Piaget states that to know an object does not mean copying it, but acting upon it. When we act upon objects, part of our knowledge is derived by the object, whilst the other part is derived by the action itself, which inserts the object into a system of transformation. What Piaget’s and Lévi-Strauss’ theories have in common is that they describe a dynamic relationship between things and thinking, positioning objects as active rather than passive life presences. What is it about objects which so strongly animates us that we, in turn, end up animating the objects? Whilst we might dismiss magical thinking about objects as an experience of childhood, the power objects exert upon us never quite ceases to exercise its influence. The objects that accompany us through our lives essentially outlive us, carrying a vast archive of singular human gestures that endow them with their unique essence. In dealing with things that have been left behind by our dead, it is not much the visual but the tactile which provides a posterior connection to whom we have lost - our hands discovering the surfaces which have been touched before; the gesture repeated in a ritualistic manner stretching through generations; an imaginary contact between our body and the body which we can no longer touch. These gestures, whilst invisible in Watkins’ photographs, are implicitly contained within the images, contaminating visuality with touch. It is through these haptic and visual experiences that Watkins seems to reinforce his familial bonds, lending to the project a performative quality in which the relationship between action and object activates the process of unforgetting. Watkins’ compositions are not merely an aesthetic practice, but a passionate practice imbued with a high emotional intensity.

In suggesting that we deal with the loss of objects and subjects in similar ways, the psychodynamic tradition underlines the complex similarities that unite how we relate to the animate and to the inanimate, offering a language to interpret our connection to the world of things. Whether dealing with subjects or objects, we confront the other and shape the self [3]. What The Unforgetting teaches us is that it is not much the loss of specific, real-life memories which constitutes the abyss of forgetting, but the loss of one’s own subject position in relation to events which are only partially remembered - or partially forgotten. Whether these subject positions are built on empirical facts or imaginary (re)connections, perhaps, is totally irrelevant. What matters in the memorialization of the dead is the opportunity do renew and revive our affective bonds, which we actualise (also) through object intimacies. That, then, would be unforgetting.

[1] Chris Marker, Sans Soleil (1983), cited by Peter Watkins, The Unforgetting (2016), interview with Pauline Rowe

[2] Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind (1962)

[3] Sherry Turkle, Evocative Objects (2007)